What if you only had an 87% chance of reaching your 5th birthday?

For most of us, tomorrow seems like a guarantee. We go to bed, almost 100% positive, that we’ll see the sun in the morning.

For children in developing countries, their chance of seeing tomorrow is closer to 87%.

Approximately one in every eight children born in a developing country dies before having a fifth birthday — approximately 21 times the average rate for developed countries.

That’s 15,000 children dying every day from preventable causes.

Or 5.5 million children annually.

The suffering of children remains a tremendous issue, yet these tragedies don’t receive the justice they deserve. Single events, such as domestic riots, always make the headlines. Daily tragedies, even ones like the deaths of thousands of children, never make the headlines.

An Overview of Child Mortality

What is child mortality?

Child mortality is the mortality of children under the age of five.

The child mortality rate (CMR), also called the under-five mortality rate, refers to the probability of dying between birth and exactly five years of age expressed per 1,000 live births.

In the past, it was very common for parents to see children die, because both, child mortality rates and fertility rates were very high.

In Europe, in the mid 18th century, parents lost on average between 3 and 4 of their children.

Today, the world has done a great job of reducing the overall number of deaths.

Since 1990, the global under-5 mortality rate has dropped by 59%, from 93 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 38 in 2019. This is equivalent to 1 in 11 children dying before reaching age 5 in 1990, compared to 1 in 27 in 2019.

But, progress hasn’t been equal.

For many countries, the child mortality rate has barely changed since 1990.

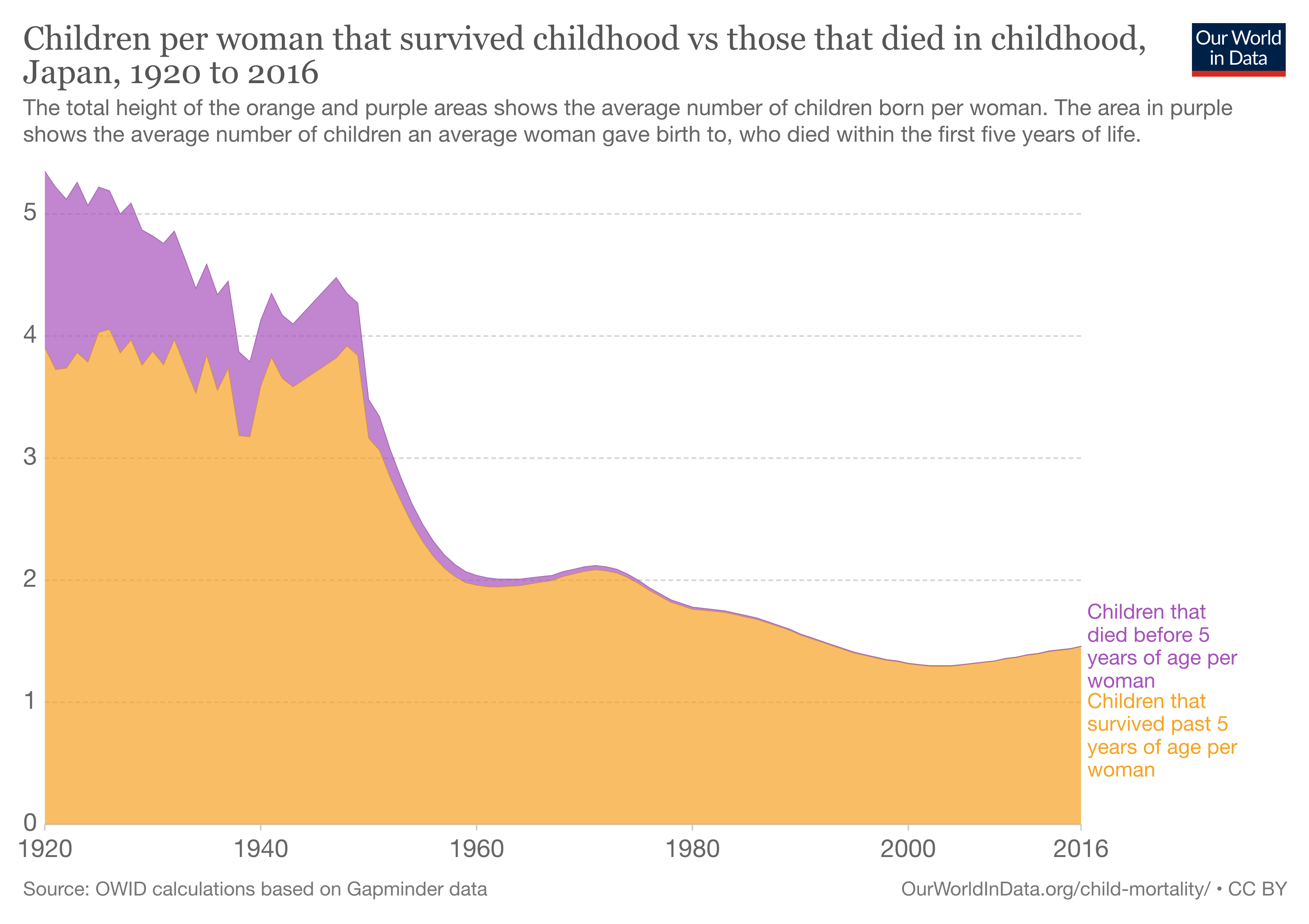

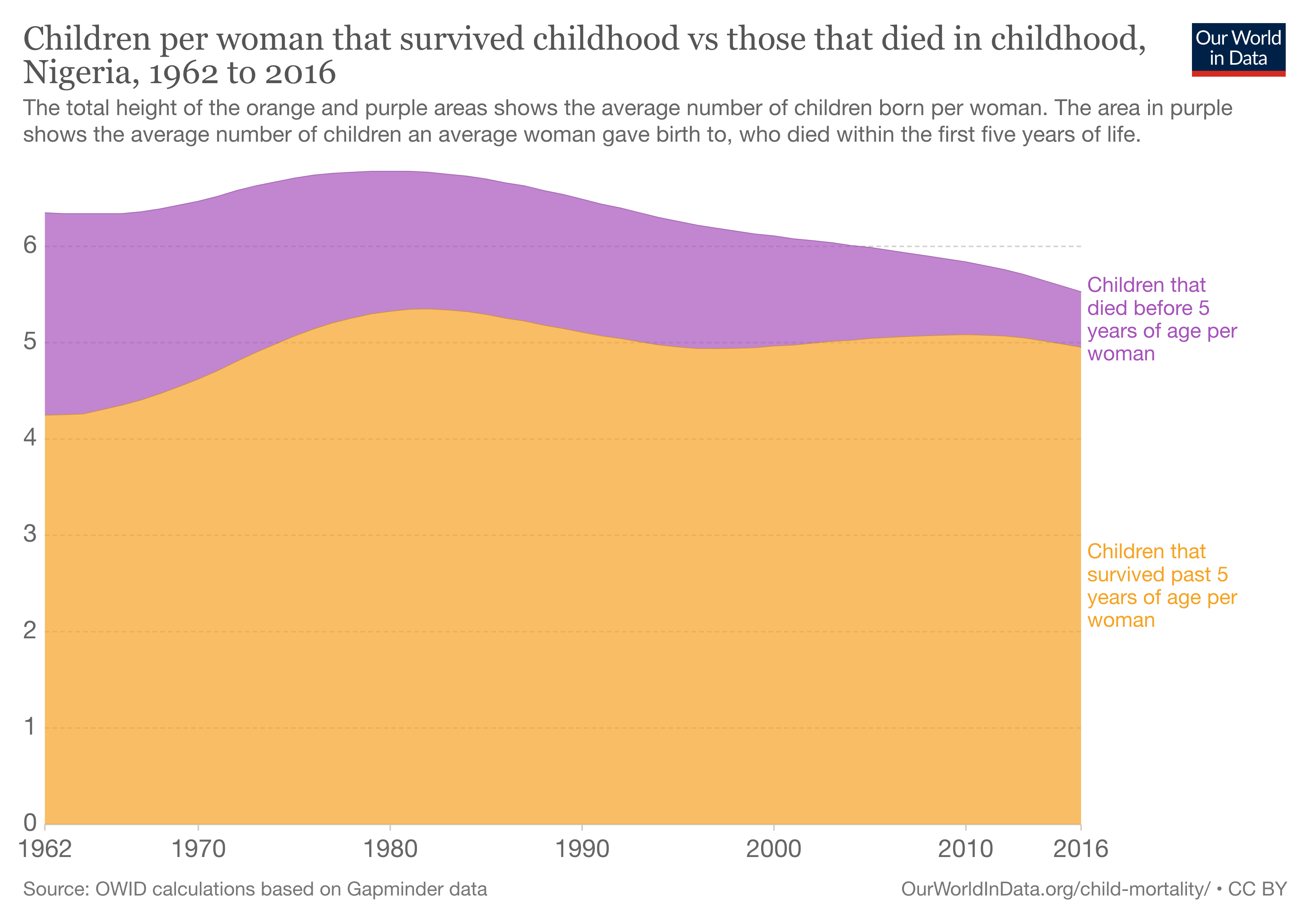

Child per women that survive in Japan vs. Nigeria 1920–2016

Remember how I said children in developing countries have a 13% chance of not seeing tomorrow. In Sweden, that chance is only 0.006%.

Their child mortality rate is <2 children out of every 1,000. According to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, a successful child mortality rate is as low as 25 per 1,000 live births.

If the entire world had Sweden’s mortality rate, we’d save 99.9% of all children.

But the entire world doesn’t have Sweden’s healthcare. People in Sub-Saharan Africa don’t have the facilities, funding, or technology that people in Sweden do. How can we expect their child mortality rate to be the same?

Children in Nigeria go here if they’re feeling ill.

A child in Sweden can go here.

Children aren’t dying because there was no treatment. They’re dying because of their circumstances.

These are PREVENTABLE deaths.

Here are the leading causes of under-5 mortality:

- Malnutrition (45%)

- Pneumonia (20%)

- Preterm birth complications (16%)

- Diarrhea (12%)

- Interpartum-related events (8%)

- Malaria (7%)

- Neonatal sepsis (5%)

These are not things that people die from in the developing world.

In 1900, the top 3 causes of death in the US were infectious diseases — pneumonia and flu, tuberculosis, and gastrointestinal infections. Spot the similarity?

The reasons people died in the US in 1890 are the same reasons children in Sub-Saharan Africa are dying today.

*This isn’t a matter of incurable cancers or life-ending injuries. Children are dying from diseases the Western world eradicated 100 years ago.*

Some countries have not changed since the 19th century.

Improvements in sanitation, vaccination development and delivery, and medical treatments, such as antibiotics, led to dramatic declines in deaths from infectious diseases during the 20th century.

This wasn’t extended to every country.

In fact, 50% of all under-5 deaths are in just 5 countries: Nigeria, India, Pakistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Ethiopia. Nigeria and India alone account for almost a third of all deaths.

But, even the average rates of death in these countries don’t reflect how bad the situation truly gets. For example, Northern Nigeria is less urbanized than Southern Nigeria, leaving their average CMR around 118 deaths per 1,000 births (40 deaths higher than Southern Nigeria).

In these regions, children don’t have the proper nutrients, healthcare, or living situations to make their chances of seeing the next day 100%.

Children are often given small portions of rice and beans as their meal

How can we stop child mortality?

The World Economic Forum recognizes the best way to reduce child mortality as taking advantage of two resources:

- Improving access to immunization

- Increasing exclusive breastfeeding rates

These two resources are readily available and, if properly implemented, can save millions of lives annually.

Improving Immunization

For the past few centuries, infectious diseases have been one of the major causes of child deaths, but the success of vaccination and antibiotics has made significant strides in reducing mortality from infectious disease.

Measles vaccination is a perfect example: the number of measles cases has shrunk by 86% since 1990. The WHO has estimated that between 2000 and 2017 measles vaccination has prevented 21.1 million deaths across Africa.

Today we also have vaccines available for tuberculosis, meningitis, hepatitis, and whooping cough–the leading causes of child mortality.

Pros:

👍 Only needed once

👍 Effective 90–99% of the time

👍 Doesn’t require parental cooperation

👍 Healthcare facility is not necessary

Cons:

🚫 Lack of healthcare infrastructure

🚫 Cost

🚫 Inability to reach healthcare centers

🚫 Need to get vaccinated for each illness

Despite the vast benefits of vaccines, only 80% of people have access to them. And most of this is 80% is in the Western world…

The developing world’s healthcare systems are not built for widespread immunization.

In a conversation I was having with Adetunji Busayo Henry, a local Nigerian child mortality enthusiast, he said plainly:

“There is almost no healthcare infrastructure in rural Nigeria.”

The cost of newer vaccines is between $3.50 USD and $7.50 USD per dose (if procured through UNICEF) and sometimes more.

To put that in perspective, more than 82 million Nigerians (42% of the population) live on less than $1 a day, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

Not only can people not access it, the government can’t store it.

Countries postpone the introduction of these vaccines because they do not have the capacity. Some countries actually delay the time for the vaccines to arrive, even when they have been paid for by others, because they do not have the capacity either at the central level or in the country.

The WHO writes that the most pressing concern is shortages of vaccine supplies to meet demand for children who turn up for vaccination sessions.

Transporting vaccines to remote areas can also be a logistical nightmare. Using bikes in South Sudan, on foot in Nepal, by donkey in Yemen or over water to far flung villages in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

And most of these governments don’t make health a priority. For example, in Pakistan, the government spends less than 1 percent of the GDP on healthcare despite having the highest infant mortality rate in the world.

Increasing Exclusive Breastfeeding

Before we get into why it’s import, let’s define exclusive breastfeeding.

Exclusive breastfeeding is defined as feeding infants only breast milk, be it directly from breast or expressed, for the first six months of their life.

Exclusive breastfeeding provides natural antibodies and immunization against diseases including diarrhea and pneumonia. Best of all, mothers create new antibodies in real time, which help strengthen young immune systems.

It’s a naturally-produced vaccine against respiratory and infectious diseases while providing all the nutrients a child needs to avoid malnutrition.

The WHO recognizes exclusive breastfeeding as one of the essential actions for infant development and survival.

Low exclusive breastfeeding rates are directly correlated with high rates of child mortality.

For example, Somalia has the second-lowest breastfeeding rate in Africa alongside the second-highest child mortality rate.

In many regions, mothers do not have access to birthing centers, hygienic nursing, and trained professionals. Breastfeeding is something almost every woman can do, regardless of their resources.

Pros:

👍 All-in-one immunization

👍 No cost

👍 Almost all mothers can do it

👍 Healthcare facility is not necessary

Cons:

🚫 Mother needs to sustain for 6+ months

🚫 Work environment makes breastfeeding hard

Why aren’t women breastfeeding now?

Only 40% of infants worldwide are breastfed exclusively until they are at least six months old, as the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends.

I said that “almost every woman” can breastfeed. There are some medical instances in which a mother cannot initiate or solely rely on breastfeeding.

Luckily, only 1 to 5 percent of women are physically unable to produce enough milk to feed their babies.

Causes of Low Breastfeeding

- The mother received misinformation (or no information) about breast and formula feeding.

- The mother did not have access to supportive care.

- The mother has postpartum anxiety or depression.

- The mother’s work and social environment do not allow for pumping breaks.

Sometimes mothers have exhaustion, depression, or physical weakness following postpartum surgery while others lack the medical or social support to navigate the logistics of breastfeeding.

Mothers often have to feed their children during the workday

ALL of these reasons are not medical. They’re problems with how society and their environments handle breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding works best when mothers have a knowledgeable and nurturing community to help them work through the inevitable questions and problems, as well as a supportive work environment, but many mother don’t have this.

The UN report finds that boosting the breastfeeding rate to 50 percent–just 10 percent–by 2025 would save the lives of 520,000 young children.

We can solve this today.

The resources exist. Breastfeeding and immunization are not revolutionary, new ideas. This is an awareness issue.

Child suffering from malnutrition

Children are placed in tubs immediately after birth.

Key Takeaways

- Since 1990, the global under-5 mortality rate has dropped by 59%, but countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia have barely changed in the last 30 years.

- Healthcare facilities and treatment in the developing world has barely changed since the 19th century

- If the entire world had Sweden’s mortality rate, we’d save 99.9% of all children.

- 5 countries (Nigeria, India, Pakistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Ethiopia) comprise 50% of global child deaths.

- Immunization and exclusive breastfeeding are the best two readily-available resources that have the capacity to eradicate the common disease.

- The solution for child mortalty already exists. We need to create awareness and creatively implement these solutions.